In downtown Seattle, you’ll notice a significant number of high-rise residential tower projects under construction. Many of these projects are designed by Weber Thompson, for example: Viktoria [+240′]; 815 Pine [+440′]; and 2030 8th Avenue [+440′]. For a host of reasons, residential towers like these are typically constructed of concrete-framed, sheer-core structures enclosed with glassy curtain walls, whereas commercial office towers are typically constructed of steel-framed structures with concrete cores.

Viktoria on 2nd Ave in downtown Seattle was designed by Weber Thompson

Building Codes classify structures as “high-rises” for the purpose of life-safety and fire-protection requirements the moment a structure contains an occupied floor located more than 75 feet above the lowest level of fire department access at street level. For smaller projects, this classification will increase construction costs by at least 5%, which is problematic for structures that are less than 12-stories tall. This is generally considered to be the point at which this extra cost for high-rise construction requirements starts to pencil out due to a higher unit count and yield.

But does this mean that middle range of eight to twelve stories should be completely ignored? There are a number of areas in Seattle with a 120’ – 125’ height limit that allow buildings of this size, but for developers looking to reach the limit on these properties, there aren’t currently many cost-effective construction options. Often, despite the goal of “highest and best use” for a site, and a goal of increased density for the downtown core from public and private sectors alike, height maximums are forfeited in favor of lower-cost construction methods, and buildings in these zones top out at seven levels. But what if there were an alternative?

This is exactly what several Weber Thompson employees are trying to figure out. Under the leadership of Scott Thompson, a team including Myer Harrell, Kirsten Clemens, Rick Nishino, Emily Doe, and Jeff Sander has been taking a close look at the pros and cons of cross-laminated timber (CLT) products. The team has been researching how CLT can be used to pre-fabricate modules, which can be assembled into taller buildings that could easily reach 125’ zoning height limits. It’s a promising step towards a solution for a common development conundrum.

Cross Laminated Timber graphic

Cross-laminated timber is relatively new on the engineered wood products scene, and there are only a handful of manufacturers in North America who make and distribute CLT products. Available in typical widths as large as 10’ by 60’ and as thick as 20″, the material is made up of dimensional lumber that has been glued together with structural adhesive and stacked in sheets with perpendicular orientation. Think of it like a Jenga tower glued solid, only the pieces are longer and the tower can only be about nine layers tall. The result is an engineered wood product with thermal, acoustic, and finish benefits, that is also the primary building structure.

Photo of cross laminated timber

Using a current WT project as a conceptual case study, the group worked in close collaboration with other industry professionals including Hans-Erik Blomgren at ARUP and Chris Angus at Sellen. They are convinced that CLT could have several major advantages over steel and concrete construction, the most cost beneficial being a quicker construction schedule. The team is working to determine the real-world feasibility of building with CLT modules that are stacked on site. “Until now, modular construction and CLT have been studied and executed in isolation, but never in this combination,” says Harrell, who has a passion for sustainable design and won the AIA Seattle Young Architect award in 2011. “In order to really gain momentum, we’ll need to formalize a code alternate or code revision with the City of Seattle, and then work with an eager developer and contractor who are willing to go outside the boundaries of conventional building,” says Harrell.

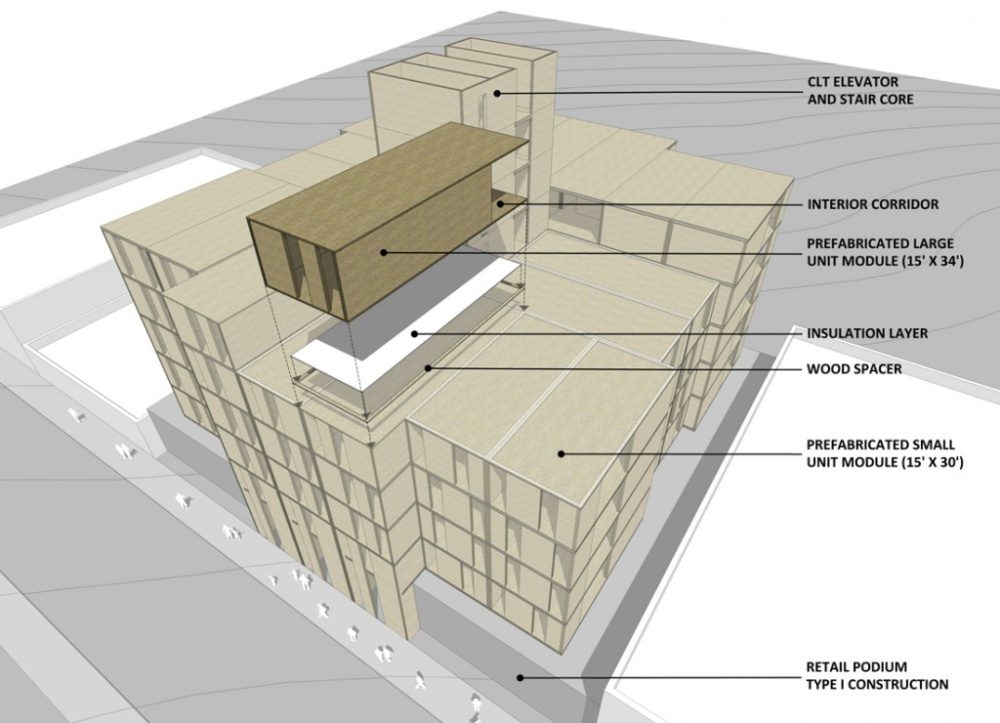

Cross laminated timber building diagram

The biggest barrier to this construction method is that it requires retooling and rethinking an otherwise standard process. In the factory, constructing a modular CLT building would resemble an assembly line more than a building, and on site, the crane would resemble an industrial shipyard, stacking containers rather than raw materials. The modules would be easy to move by ship or truck, and they could be stacked quickly with the right tools, dramatically reducing construction time and associated land-carrying costs.

No one knows exactly how many under-utilized parcels could benefit from this construction type in Seattle, but the idea is gaining momentum here and in Canada. A company in British Columbia, Canadian Sustainable Timber Innovations, is manufacturing CLT products and the primary source of the wood is beetle kill pine. The abundant source of wood coupled with support from the Canadian government is helping the product gain popularity. In Melbourne, an apartment building was recently completed that has a concrete podium with nine levels of CLT, and they created a time-lapse video to document the construction process.

While owners may be excited by the niche application of modular CLT in a difficult zoning designation, and contractors will be challenged by new materials and methods on a shortened schedule, it is the sustainability and aesthetic aspects that appeal most to architects. When forested or recycled responsibly, wood has long been understood as a renewable resource with a net carbon reduction to the environment as analyzed in its overall lifecycle, things that neither steel nor concrete can claim. The ability to build more densely out of wood is a win-win for the green building movement. And, when detailed to expose the wood in walls and ceilings, CLT can help bring the warmth and beauty of wood finishes to high rises, achieving an honesty of structure to which architects often strive.

Cross laminated timber building diagram

If it turns out that the Weber Thompson team’s modular CLT approach is financially and environmentally beneficial, this method could be just the thing to fill the eight to twelve story void in Seattle. Our team and others will continue their research, testing and applying new methods to case studies, quantifying anticipated benefits, and working toward a pilot project in Seattle. It is one of the ways we keep thinking outside the box to promote the values of innovation and sustainability that are core to our mission here at Weber Thompson. If it results in a physical project, then that’s the cherry on top.