By Rachael Meyer

Treated stormwater runs in Rachael Meyer’s blood. Leading Weber Thompson’s Landscape Architecture and Sustainability Design teams, she harnesses the passion of others to better our environment.

The Aurora Bridge Swales project took home the Honor Award in the General Design, Private Ownership category at the 2022 WASLA Awards. The project was recognized by the judges for the excellent detailing, great planting choices, and thoughtful incorporation of educational materials.

The Aurora Bridge Swales

THE SWALES ARE BUILT ADJACENT TO THE AURORA BRIDGE, AN HISTORIC STRUCTURE IN SEATTLE WHERE ALL FIVE OF THE REGIONS’ SALMON SPECIES SWIM TO REACH THE NETWORK OF RIVERS AND STREAMS WHERE SPAWNING OCCURS EACH YEAR.

The Aurora Bridge Swales highlight the value of green infrastructure in urban areas and demonstrates the need for urban development to improve upon conventional practices to restore the health of the natural environment. This project in an example of how landscape architecture can serve as a change agent, providing communities a call to action, to improve the health of our world.

Urban populations are growing as are the number of cars on roadways and the amount of toxins entering the environment. Within the past six years, researchers in the Pacific Northwest have identified thousands of chemicals present in urban stormwater runoff including toxins specifically responsible for the drastic decline of salmon populations in the Puget Sound.

As an indicator species, salmon serve as a signal to the overall health of the marine environment. A dramatic decline in Pacific Northwest salmon populations spurred researchers at Washington State University to study the effects of stormwater runoff on the health of aquatic environments. The findings were dramatic, conclusively linking roadway runoff with the death of salmon. However, the expected culprits such as heavy metals and petroleum proved not to be responsible for the fatal outcome. What was discovered in the research was the effectiveness of using soil to filter out the toxins, eliminating the fatal effects on the test subjects.

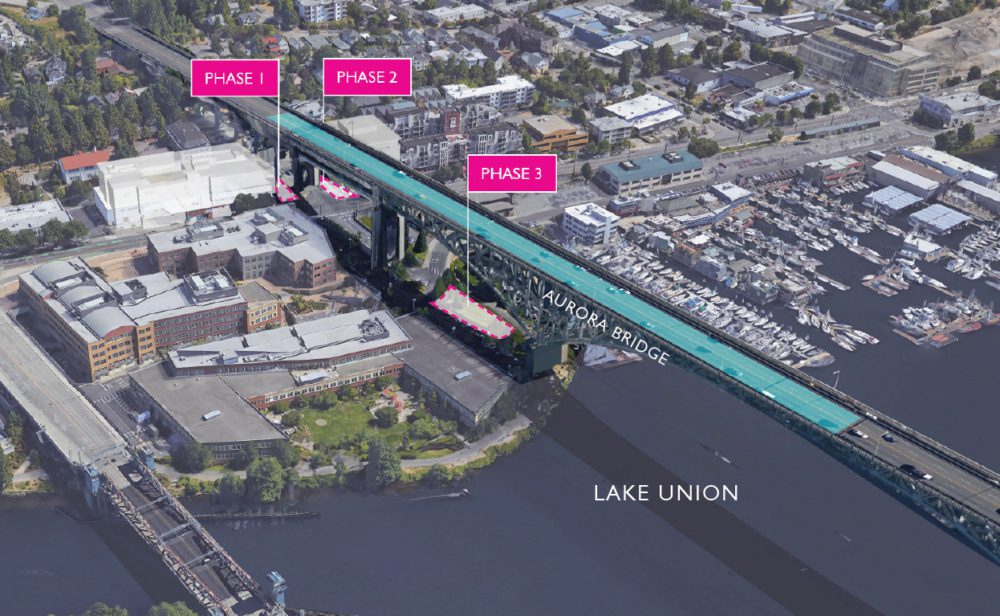

Phase 1

At the same time as the preliminary research was published, the project team of a new commercial office development in the Fremont neighborhood of Seattle, WA was assembling. The team was inspired by the WSU research and wanted to see how they could apply it to their new building. The proposed building site was directly adjacent to and below the Aurora Bridge, an historic structure in Seattle under which all five of the regions’ salmon species swim to reach the network of rivers and streams for spawning.

THE AURORA BRIDGE SWALES PIONEERED THE USE OF GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE BY PRIVATE DEVELOPMENT TO IMPLEMENT ENVIRONMENTAL RESTORATION ON A LARGER SCALE.

The initial idea was simple: leverage the project’s adjacency to the bridge, divert a downspout from the bridge into a planted area and clean the water before it reached the salmon.

Incorporating this strategy into the project underscored the client’s philosophy of sustainable design, as evidenced in their development of both LEED certified and Living Building projects. Both the developer and prospective tenant espoused high ideals regarding the way work environments could support healthy living by incorporating large bike amenities, visual and physical access to nature and use of healthy materials into the project goals early on. When the design team considered the improvement options for the historically dark and unappealing area below the bridge, the team zeroed in on ways to clean up the streetscape.

EMBRACING THE STEEP GRADE OF THE ROADWAY, THE SWALES STEP AND OVERFLOW THROUGH CORTEN STEEL WEIRS WITH EVERY TWO FEET OF GRADE CHANGE.

The solution was to locate a swale on a steep roadway rather than creating settling pools used in more conventional green infrastructure. Embracing the steep grade of the roadway, the swales step and overflow through Corten steel weirs with every two feet of grade change. The use of steel is echoed in all phases, with custom details expressing the water story throughout. Native plants provide a robust forest floor below the overhead canopy that the bridge structure and columns simulate. Flowering plants were prioritized supporting many species of pollinators in the area.

Several barriers complicated the process, most significantly the multiple municipal agencies involved and the lack of precedence for a private development to propose improvements that reached well beyond the property boundary of the site.

The stormwater that falls on the Aurora Bridge changes jurisdiction many times before its outfall into Lake Union. Initially, rain falls onto the Washington State-owned bridge where it flows into downspouts, which are owned by the state but maintained by the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT). The downspouts end about one foot above the street below, where jurisdiction shifts solely to SDOT before entering a catch basin leading to a storm drain managed by Seattle Public Utilities, a subdivision of SDOT. When the storm drain crosses into a shoreline buffer within 200 feet of the water’s edge of Lake Union, the Department of Ecology adds another set of requirements and permits to navigate that includes a below-grade outfall at the edge of the lake.

The simplicity of temporarily diverting stormwater was critical in gaining support from the many review agencies. It avoided disputes over water rights or issues that might disenfranchise downstream users considering the significant water quality improvement.

Phase 2

WITH A CLEARER PATH FOR PERMITTING, EACH PHASE BUILT UPON THE PRIOR’S SUCCESS CLEANING MORE WATER AND INCREASING PUBLIC AWARENESS.

The second phase of the swales’ construction occurred when the same design and development team proposed another office building on the opposite side of the bridge. With a clearer path for permitting, and precedence to rely on, the project elected to divert two downspouts, and take on the larger project goal of eliminating the use of potable water for non-potable uses within the building. The project installed a 20,000 gallon cistern to collect roof runoff and used the swale to slow and filter cistern overflow, which occurs about four months out of the year.

Phase 3

PHASE THREE INCLUDES A NEARBY PROPERTY WHERE FIVE ADDITIONAL DOWNSPOUTS COULD BE DIVERTED INTO A GRASSY AREA. THIS PHASE INCREASED THE VOLUME OF FILTERED BRIDGE WATER TO TWO MILLION GALLONS, EFFECTIVELY TREATING THE NORTH HALF OF THE ABOVE BRIDGE DECK.

At the same time as the design of the second phase, a nearby property was identified where five additional downspouts could be diverted into a grassy area. The third phase increased the volume of filtered bridge water to two million gallons, effectively treating the north half of the bridge deck above. The goodwill and relationships built during the first and second phases helped to secure donations from other Fremont businesses as well as a matching grant from the state government.

Testing of the water entering and leaving the swales confirmed measurable filtration of a large range of contaminants. As the third phase neared completion, researchers announced they successfully isolated the specific chemical responsible for the death of salmon seen in the earlier studies. The chemical, called 6PPD-quinone, is derived from a preservative found in all tires.

MEASURABLE TESTING CONFIRMS THAT AS THE WATER FILTERS DOWN THE SWALES IT BECOMES CLEANER AND LESS CONTAMINATED.

An added layer of benefit to this project is its replicability. When bridges align with a roadway below, as occurs with most urban bridges, green infrastructure is especially efficient when the overflow at the end of the swale can connect back to the existing storm pipe infrastructure that previously carried the unfiltered water to the lake. This can save municipalities from spending money mechanically filtering the water at expensive treatment facilities.

The Seattle Public Utilities has begun programs to incentivize similar improvements with private developments. A case study of the swales has been included in a United Nations Guide for Sustainable Practices as a model to teach professional designers to include green infrastructure as standard practice.

A CASE STUDY OF THE SWALES IS INCLUDED IN A UNITED NATIONS GUIDE FOR SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES AS A MODEL TO TEACH PROFESSIONAL DESIGNERS TO INCLUDE GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE AS STANDARD PRACTICE.

Public awareness of these strategies is also reinforced through a commitment to public signage that has taken on many forms. Brass numbers embedded in the sidewalk illuminate the amount of water each swale cell mitigates, while brass plaques illustrate the many benefits of the strategies employed in a relief that can produce rubbings. Laser cutouts of the silhouettes of the five salmon species cue pedestrians to the greater story of how, through smart development and design, we can help restore the aquatic environment.

Learn more about the Aurora Bridge Swales